54. Puerto Maldonado

Unfortunately, I don’t get through the metal detector unscathed. The guy starts checking me with the metal-detecting wand, and in my right pants-pocket – oops! – is the Swiss army knife that has lain there, unnoticed except when needed, for six months. Gone. Then the lady checking my bulging backpack discovers my second Swiss army knife, stashed conveniently in a small compartment and forgotten, since I haven’t lost or misplaced the one in my pocket. Two Swiss army knives gone in a moment – just when I’m going where they might be useful!

When I board the plane, there’s a family of three in the row where I’m meant to have the window seat. Too bad. But I wait patiently and do get a seat. I start reading Garcilaso.

It’s interesting reading. I recommend it. Garcilaso writes of the Incas from a unique viewpoint: his father was one of the conquistadores with Pizarro, his mother was an Inca princess, and her family taught him much about the old culture that the Spaniards did not know. He grew up in Cusco, very soon after the Conquest. Of course, being a Christian, and having moved to Spain before he was 20, he wrote with some interest in making the Inca appear no more savage than necessary to European eyes. He’s not unbiased. But his account is interesting, knowledgeable, and believed to be generally accurate. (He’s also significant as the first important Latin American writer.)

The Inca mode of conquest seems to have been to march up to the edge of your territory with a force sufficient to destroy you, then parlay. They sent in emissaries to explain why their religion, engineering, customs, and social organization were superior to anyone else’s, and point out that it would be in your interest to join the Inca empire rather than resist it. Obviously this argument was buttressed by the fact that they had brought a force sufficient to kick your ass. Still, they parlayed fairly patiently, and often conquered new territory without the need for violence. When violence did ensue, they were up to it, and ultimately prevailed; but even then they were relatively forgiving. They took your leaders to Cusco to learn to be good Inca administrators, then sent them back as such. (Even if Garcilaso exaggerates a bit, this seems to be basically accurate.)

There was one exception, which I mention not to make anyone uncomfortable but because I think it’s worth knowing, particularly among those who have questions concerning Peru’s reputation for what is now called “homophobia.” The exception: occasionally the Inca conquered a region in which homosexuality was widely practiced — or was believed to be. In this case they killed every homosexual; and the wife and children of any homosexual, if he had any; and all of his livestock; and burned his home and crops.

From the moment we land, and as we ride the noisy moto-taxi in from the airport, Puerto Maldonado is just as I imagined it – no, knew it – to be, from some haphazard collection of dreams, filmic images, and mental visions formed while reading.

What flies past us on the way into town is not beautiful: a lot of motorcycles and moto-taxis, few cars, several grifos,

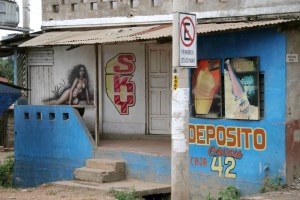

What flies past us on the way into town is not beautiful: a lot of motorcycles and moto-taxis, few cars, several grifos,  the sloppy greenery of the jungle, simple buildings

the sloppy greenery of the jungle, simple buildings  and houses, most of wood and some on stilts, and occasional food stores surrounded by motorcycles.

and houses, most of wood and some on stilts, and occasional food stores surrounded by motorcycles.

It feels different, not merely because of the lower altitude or the humidity. (The air is warmer and heavier.) This is an engaging and unpretentious place. It is quite distant, of course, from Peru’s major cities, let alone the more famous cities elsewhere. More, it feels influenced by the jungle and the climate.  None of the buildings is beautiful or elegant or complex, perhaps because one feels here that the jungle will reclaim everything soon enough. No one is dressed elegantly or drives a fine car. The muggy weather, the intermittent rain, and the mud would sabotage finery, and probably rusts cars. It seems a place not at all of indolence, but where the heat and humidity and mud and

None of the buildings is beautiful or elegant or complex, perhaps because one feels here that the jungle will reclaim everything soon enough. No one is dressed elegantly or drives a fine car. The muggy weather, the intermittent rain, and the mud would sabotage finery, and probably rusts cars. It seems a place not at all of indolence, but where the heat and humidity and mud and  jungle are too dominant to permit pretentions. The finest clothes would be stained by mud and sweat here, and the finest cars crippled by the roads and rust.

jungle are too dominant to permit pretentions. The finest clothes would be stained by mud and sweat here, and the finest cars crippled by the roads and rust.

We check in at Don Carlos’s, which overlooks the Rio Tambopata. Its most impressive feature is a green parrot who hangs around on the terrace while you are drinking coffee. It is perhaps the best hotel in town.

Almost immediately I set out to walk to the Plaza de Armas. It is a long walk on a fairly warm Sunday. Domingo. I am alone. Almost all stores are closed. Still, I feel energized, curious about my new

Almost immediately I set out to walk to the Plaza de Armas. It is a long walk on a fairly warm Sunday. Domingo. I am alone. Almost all stores are closed. Still, I feel energized, curious about my new

surroundings. Too, my mood is odd: the domestic tension and uncertainty make it somber, but fresh solitude in a new place lends it a certain excitement. Traveling alone is always different from traveling in a

surroundings. Too, my mood is odd: the domestic tension and uncertainty make it somber, but fresh solitude in a new place lends it a certain excitement. Traveling alone is always different from traveling in a  group or couple: one is freer to follow chance encounters

group or couple: one is freer to follow chance encounters  where they lead, and able to munch on and digest one’s impressions before conversation dilutes them.

where they lead, and able to munch on and digest one’s impressions before conversation dilutes them.

It’s a pleasant and solitary walk. Even with most businesses closed, the walk to the Plaza de Armas is marked by colorfully painted

It’s a pleasant and solitary walk. Even with most businesses closed, the walk to the Plaza de Armas is marked by colorfully painted

buildings and lively music. Children are out playing. Moto-taxis ply their trade. Toward the end of the walk, a tall statue of Mary watches over the Plaza.

buildings and lively music. Children are out playing. Moto-taxis ply their trade. Toward the end of the walk, a tall statue of Mary watches over the Plaza.

I find a pleasant ice cream shop, and sit near a window eating chocolate ice cream and taking occasional pictures, mostly of whole families on motorcycles. This is nothing new (decades ago in Taiwan it was like that, and I was guilty of it too, carrying both my girl friend and a tall friend of ours on a little 125 cc. bike), but seems even more extreme here. Soon I also realize that a lot of the motorcyclists I see stopping for friends are actually motorcycle-taxis. The passenger climbs on the back of the bike, sans helmet, and pays a few soles for a ride.

I find a pleasant ice cream shop, and sit near a window eating chocolate ice cream and taking occasional pictures, mostly of whole families on motorcycles. This is nothing new (decades ago in Taiwan it was like that, and I was guilty of it too, carrying both my girl friend and a tall friend of ours on a little 125 cc. bike), but seems even more extreme here. Soon I also realize that a lot of the motorcyclists I see stopping for friends are actually motorcycle-taxis. The passenger climbs on the back of the bike, sans helmet, and pays a few soles for a ride.

I also spot a place to rent scooters, and resolve to do so the next day.

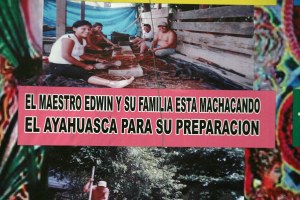

Around the corner from the scooter-rental shops, a pleasant-looking hotel overlooks the other river, the Madre de Dios. It’s the Hotel Wasi. I arrange to move there the following day, thus complying with Ragna’s desire to have me stay in some other hotel. The Wasi overlooks the other river, the Madre de Dios, not far from where the  ferry boats dock. I walk down there, past the sign for the local shaman.

ferry boats dock. I walk down there, past the sign for the local shaman.

Resisting the lure of the maestro’s sign, I walk a few steps further and see an appealing

Resisting the lure of the maestro’s sign, I walk a few steps further and see an appealing  composition: a shop wall painted bright red as a Coca Cola ad, with a few children, a bicycle, and a dog approaching it. I pause, waiting for them to reach the sign, and notice the shop to my right, with very different advertisement painted on it.

composition: a shop wall painted bright red as a Coca Cola ad, with a few children, a bicycle, and a dog approaching it. I pause, waiting for them to reach the sign, and notice the shop to my right, with very different advertisement painted on it.

It’s a visually interesting spot, just a few meters from the entrance to the Madre de Dios ferry. I shoot a couple of shots of the kids and the Coke sign, realizing that part of its appeal is its contrasting associations for me: it’s half some Norman Rockwell picture of kids by a barn with a painted coke sign three-quarters of a century ago, and half this frontier river town in the jungle. Another motorcycle family passes them and  decides to stop and be part of the picture. It’s such a magical spot that the next motorcycle to pass actually has a family of five on it, trumping anything I shot at the Plaza.

decides to stop and be part of the picture. It’s such a magical spot that the next motorcycle to pass actually has a family of five on it, trumping anything I shot at the Plaza.

When I reach the long stairway down to the ferry, I learn that it costs half a sole to cross. I walk up the wooden plank from the mud, to general amusement: I’m the only foreigner; in fact, I’m the only foreigner I see on any of the ferry boats I ride or see in Puerto Maldonado, except for one minibus-ful of French-Swiss people traveling with a guide.

When I reach the long stairway down to the ferry, I learn that it costs half a sole to cross. I walk up the wooden plank from the mud, to general amusement: I’m the only foreigner; in fact, I’m the only foreigner I see on any of the ferry boats I ride or see in Puerto Maldonado, except for one minibus-ful of French-Swiss people traveling with a guide.

Note Rambo’s universal appeal. Decades ago, now, I was walking past Lhasa’s magnificent Potala Almost no one in Tibet spoke any English then, and few even spoke much Chinese.

Note Rambo’s universal appeal. Decades ago, now, I was walking past Lhasa’s magnificent Potala Almost no one in Tibet spoke any English then, and few even spoke much Chinese.  Nevertheless, among the shops and restaurants and chang spots along the street at the base of the Potala, one establishment was proudly labeled “Ranbo Bar.” The misspelling added to the effect.

Nevertheless, among the shops and restaurants and chang spots along the street at the base of the Potala, one establishment was proudly labeled “Ranbo Bar.” The misspelling added to the effect.

I’m in the mood to shoot everything I see. The boats tied up to the dock, the boats approaching from across the river, the ferryman, my fellow passengers. I’m like a child, looking at everything with wonder, and my fellow passengers seem to know that – or they’re unaccustomed to an old gringo wandering onto a passenger ferry alone. Is this another place where the tourists are all clumped together in minivans, riding the larger ferry and grouped around a guide? In any case, the men on the ferry boat greet me, grin, remark on the camera. I confess to taking a great many photographs, and as they see how true that is some of them laugh.

Soon after we push off, I spot a huge concrete structure – at least, it looks pretty huge from a small boat on the river – that must be a support for a planned bridge over the river. I ask the boatman, who confirms that it’s for a bridge. The bridge may change his life. It must be for the Trans-_____ Highway that’ll make the drive to here, and the drive from here to Brazil, a whole lot easier. Undoubted progress I hope won’t happen too soon. I imagine

Soon after we push off, I spot a huge concrete structure – at least, it looks pretty huge from a small boat on the river – that must be a support for a planned bridge over the river. I ask the boatman, who confirms that it’s for a bridge. The bridge may change his life. It must be for the Trans-_____ Highway that’ll make the drive to here, and the drive from here to Brazil, a whole lot easier. Undoubted progress I hope won’t happen too soon. I imagine  the boatman hopes it won’t, either. It’ll probably destroy his livelihood. Intermittently I wonder how it feels to work as you’ve worked for decades, in the shadow of a concrete reminder that you will soon be obsolete.

the boatman hopes it won’t, either. It’ll probably destroy his livelihood. Intermittently I wonder how it feels to work as you’ve worked for decades, in the shadow of a concrete reminder that you will soon be obsolete.

The future looms over the bow of the ferry

Car Ferry - Rio Madre de Dios

passenger ferries waiting at Triunfo

There is nothing special to see at the ferry-landing on the opposite bank. Just more ferry boats, more steps, a few food vendors

There is nothing special to see at the ferry-landing on the opposite bank. Just more ferry boats, more steps, a few food vendors  and what looks like a bar, and a huge logging truck. And a dirt road heading off toward wherever. Still, I walk

and what looks like a bar, and a huge logging truck. And a dirt road heading off toward wherever. Still, I walk  about, looking and listening. Then I buy a Sprite from one of the vendors — actually from a young boy spelling his mother at her stand — and sit on a rough wooden bench beside the stand.

about, looking and listening. Then I buy a Sprite from one of the vendors — actually from a young boy spelling his mother at her stand — and sit on a rough wooden bench beside the stand.

waiting

Sitting on a little unpainted wooden bench is good. My legs are old, and it gives them a rest; and it’s a kind of camouflage, allowing me to watch and listen in a lazy way, and shoot the occasional photograph; and closer around me, I have a briefly view into the lives of the vendors. The boy says nothing, but I can feel that, alternately standing and sitting behind me, he’s curious. In the next  stall a child with oddly light hair – reminding me of a Mayan girl I photographed one morning in the jungle near Bonampak – stares at me. When I photograph her, her mother watches, amused. When I approach to show the little girl her image, asking “Quien es?” in my sweetest, cajoling tone, she cries. Her mother looks at the image in the camera viewer and invites the girl to look again, but she isn’t having any, and eyes me with distrust as long as I sit there. When I turn around, the boy, whose mother has come back to the stall, is doing puzzles or something from a book. His mother leans over to help him with one, and I realize it’s a schoolbook, which he confirms when I ask. Then I notice that the dictionary is a bilingual one. He’s studying English. So I ask him

stall a child with oddly light hair – reminding me of a Mayan girl I photographed one morning in the jungle near Bonampak – stares at me. When I photograph her, her mother watches, amused. When I approach to show the little girl her image, asking “Quien es?” in my sweetest, cajoling tone, she cries. Her mother looks at the image in the camera viewer and invites the girl to look again, but she isn’t having any, and eyes me with distrust as long as I sit there. When I turn around, the boy, whose mother has come back to the stall, is doing puzzles or something from a book. His mother leans over to help him with one, and I realize it’s a schoolbook, which he confirms when I ask. Then I notice that the dictionary is a bilingual one. He’s studying English. So I ask him  about that, but he must be just beginning – or his lessons are almost purely from the printed page, and he’s had no experience actually conversing in the language yet — because even “What’s your name?” and “How are you?” draw blank stares from him.

about that, but he must be just beginning – or his lessons are almost purely from the printed page, and he’s had no experience actually conversing in the language yet — because even “What’s your name?” and “How are you?” draw blank stares from him.

It’s Sunday. Domingo. I sip my soda and enjoy life. When I finish it, now with no good reason to hang round, I descend to a ferry, and after awhile we’re headed back to Puerto Maldonado.

Now the logging truck I photographed up on the bluff is driving onto a larger car ferry, to cross the river toward wherever the logs will become boards. More consumption of rainforest trees, vital to our survival. Above, the truck full of logs was just a big thing to photograph, the biggest thing around up there, dwarfing the little houses and the motorcycles and the food stalls. On the river, it strikes me as one small part of humanity’s rape  of the rainforest. Innocuous, unnoticed, quiet, unremarkable. But part of something larger and sad. At the same time, the truck looks almost respendent for a moment in bright sunlight, carried across the river like some huge king.

of the rainforest. Innocuous, unnoticed, quiet, unremarkable. But part of something larger and sad. At the same time, the truck looks almost respendent for a moment in bright sunlight, carried across the river like some huge king.

As with certain witnesses and friends I’ve dealt with, nothing is every quite black or quite white in the rainforest.

almost home

I take a moto-taxi from the ferry area to the hotel. From the hotel I hear music, as if from some festival or perhaps a sporting event. The girl behind the desk explains that it’s a football game, a few blocks away. Having no pressing engagement, I start toward the noise.

Walking the dirt street toward the stadium, the visual surroundings are unfamiliar, but the sound and feel in the air are of a Saturday afternoon high school football game in the beautiful countryside along the Hudson River four decades ago. I am walking down uneven dirt  lanes with occasional sheep, and women gossiping in front of houses with slogans written on them, rather than the proud suburban homes of small-town North America; and the kids in short pants

lanes with occasional sheep, and women gossiping in front of houses with slogans written on them, rather than the proud suburban homes of small-town North America; and the kids in short pants  playing pick-up soccer against the wall of the stadium are not playing “one-a-cat” with a baseball

playing pick-up soccer against the wall of the stadium are not playing “one-a-cat” with a baseball  and a bat against the brick walls of Pierre Van Cortlandt Elementary School. But the energy in the air, the band music, the cheering and jeering of the crowd, are as I heard them striding toward the high school field for that different kind of football.

and a bat against the brick walls of Pierre Van Cortlandt Elementary School. But the energy in the air, the band music, the cheering and jeering of the crowd, are as I heard them striding toward the high school field for that different kind of football.

When I turn onto the street along the stadium walls, though, I am  clearly in Peru. The walls are the exceptionally tall walls Peruvians favor. But through holes, perhaps scraped into the wall for just this purpose, youths watch the distant game, as kids watched through knot-holes the major-league baseball games from Shoeless Joe Jackson’s time. And atop the high walls sit groups of men and boys, and a few women. Some have climbed, using the ridges at some levels of the wall and its natural decay. Beneath others stand wooden ladders, just high enough so that from the top rung one can pull oneself up onto the top of the all, as in a comic-strip indication of a burglary.

clearly in Peru. The walls are the exceptionally tall walls Peruvians favor. But through holes, perhaps scraped into the wall for just this purpose, youths watch the distant game, as kids watched through knot-holes the major-league baseball games from Shoeless Joe Jackson’s time. And atop the high walls sit groups of men and boys, and a few women. Some have climbed, using the ridges at some levels of the wall and its natural decay. Beneath others stand wooden ladders, just high enough so that from the top rung one can pull oneself up onto the top of the all, as in a comic-strip indication of a burglary.

I walk along, photographing the folks on the walls, and turn right to see more of them, as well as a huge delivery truck parked on the street with three men standing on top of it to watch. There are nearly as many people on top of the wall, or watching through holes or breaks in the walls, as in the stadium.

I’m an outlaw myself. I photograph one family up there, then ask if I may move their ladder slightly to the side of them and use it to join them. Of course I may. The spectacle of a middle-aged foreigner [or shall I simply say “old” ?] climbing the wall with his camera and fisherman’s vest amuses everyone in the area. My legs are not limber, and there are four rebar rods sticking up out of the wall just where I’d like to swing my legs over to let them dangle on the football-field side, but I manage.

I’m an outlaw myself. I photograph one family up there, then ask if I may move their ladder slightly to the side of them and use it to join them. Of course I may. The spectacle of a middle-aged foreigner [or shall I simply say “old” ?] climbing the wall with his camera and fisherman’s vest amuses everyone in the area. My legs are not limber, and there are four rebar rods sticking up out of the wall just where I’d like to swing my legs over to let them dangle on the football-field side, but I manage.

The game is not right below us. Several meters within this brick wall is a chain- link fence – also high, and with wire to discourage anyone from climbing over it. Inside the smaller enclosure, a team in red is playing a team in green. Legitimate “stands” are on the side of the field to my left, and

link fence – also high, and with wire to discourage anyone from climbing over it. Inside the smaller enclosure, a team in red is playing a team in green. Legitimate “stands” are on the side of the field to my left, and  in the far corner, to the right of the field, there appears to be another small grandstand. There really do seem to be a lot more people on the fence than inside it, and snack-vendors working the

in the far corner, to the right of the field, there appears to be another small grandstand. There really do seem to be a lot more people on the fence than inside it, and snack-vendors working the  game periodically walk around the perimeter to offer their wares to the spectators on the wall. (Is a seat inside costly? Or do a lot of these folks just feel that an illicit view of the game is a whole lot more pleasurable?)

game periodically walk around the perimeter to offer their wares to the spectators on the wall. (Is a seat inside costly? Or do a lot of these folks just feel that an illicit view of the game is a whole lot more pleasurable?)

At some point I ask the girl next to me whether one team is from here and another from elsewhere, or whether these are two teams from Puerto Maldonado. “Los Rojos,” she says, are from Puno. It is a long way. The players from Puno must have flown here.

As I start shooting photographs, something brushes my left shoulder lightly. It is a man who has moved the ladder a few inches from where I left it, and climbed up to sit just the other side of the protruding rebar.

I immerse myself in shooting. The game is too far away Still, it amuses me. It is what I do. Around me the game continues, with kicks and headers and penalties, but no goals; the crowd jeers at one foul, and people toss a few things off the wall onto the grass between us and the soccer field.

At some point I grow a little tired of sitting up there watching. Although I am naturally rooting for the boys in green, I can’t pretend to care very much who wins. (I do not witness a goal and do not ask whether or not any were scored before I arrived.) I haven’t played the game for years and can’t see very well from here anyway.

I glance down for the ladder, which of course is gone. Again I think of a comic-strip burglar dangling from a second- or third-story windowsill by his fingertips, a house-painter having borrowed his ladder. There are now eight or ten more people sitting to my left on this wall, and the ladder is beneath one of them. It’s a good ways from me, there’s no possibility of standing up on this wall and trying to step over people, and it’s not clear that anyone could pass it over to us without climbing down to the ground.

Of course, as soon as I see that I can’t feasibly leave, I desire even more to get away. I am a stupid old man sitting on a wall.

To my right, the young woman also gets curious about the location of the ladder. She can’t see it, doesn’t dare lean back far enough to see how far it’s traveled, and asks her boyfriend or husband or older brother. (He’s holding the child, so I’m guessing they’re parents together.) Someone on the ground manages to recover the ladder and return it to where we are, and I gratefully descend.

I walk back the way I came. There are even more illegal spectators than before, including a fellow who’s pulled his moto-taxi close to the wall to stand on its roof, and others who at first glance look as if they’re hanging by their crossed arms on top of the wall. The pick-up football game has six or eight players now, instead of three.

I walk back the way I came. There are even more illegal spectators than before, including a fellow who’s pulled his moto-taxi close to the wall to stand on its roof, and others who at first glance look as if they’re hanging by their crossed arms on top of the wall. The pick-up football game has six or eight players now, instead of three.

I have had a full, odd, useless day.

My room is appealing: large, and with a writing desk near the window, and a bit of a view of the river; but quickly I realize that some large population of dogs occupies the yard just below my window. The dogs aren’t happy, and are continuously barking their complaints to the world at large, and as I am unlikely to manage to solve their problems, I ask for another room. Unfortunately, the only inner room available is right next door to the ladies. I have no choice, if I hope to sleep tonight; but it is odd to hear their voices and laughter through the wall.

I eat alone in the dining room, reading Garcilaso. The meal is quite good. The television offers what will be the last major league baseball game ever played at Yankee Stadium. As a child, I hated the Yankees and was thrilled by the Dodgers’ upset win in the 1955 World Series. In my youth, I took delinquent kids to ball-games there, and drove cabs in the shadow of the stadium. Tonight it seems odd to be watching U.S. baseball, but I can’t resist doing so – at least Ragna and Selma come in. Then I retire to my room to write.

not bad; adequate rooms with desk and chairs and shelf space for clothes and other stuff; new wing appears to have rooms in some ways less charming but better-appointed than those in the old wing; and they have a view over a set of old houses or huts. Unfortunately, those houses or huts come accompanied by dogs, whose loud barking sent me begging for a new room by mid-evening. Nice folks. Friendly parrot. Quite good food. Modest view of the Rio Tambopata from some rooms and the front terrace.

For better or for worse, somewhat isolated. It’s a good hike to the Plaza de Armas, fun the first time but not something I’d want to have to do when I was in a hurry or carrying a large pack, or in the heat of a sunny day. However, there are usually mototaxis hanging around out front, and if there aren’t any the staff will send a young man to find one.

Hotel Don Carlos serves good suppers.

The Wasai Lodge is another reasonable hotel choice. I moved to it the next morning, to ensure domestic tranquility.

Other Points:

There are few cabs, but plenty of moto-taxis, and some motorcycles that function as cabs. The moto-taxis are fine, except perhaps in a sudden downpour.

Motor scooters can be rented fairly cheaply near the Plaza de Armas. There are four or five shops on one block. Be careful to make sure the one you get has rear-view mirrors and all! The first one I rented didn’t, and I didn’t notice it — and driving a motor scooter with no rear-view mirror and an unfamiliar gearshift system can be unnerving.